Monday, July 30, 2012

Is Anger, Like, So Over? Or, What Happened To Generation X?

Remember Nirvana? The band? "Smells Like Teen Spirit?" "Heart-Shaped Box?"

It's only been about twenty years since their massive popularity hit its peak, but in some ways their era and their music feels more foreign and far away than that of less recent musical artists. Exhibit A: The Talking Heads. See also Cyndi Lauper, Prince, and Michael Jackson's "Thriller." All feel very much "of our time."

If you go to the gym, or shop, or hang around cafes, you can hear music from pretty much every decade since the 60s. How often have you been out and said to your friend or to yourself, "Oh my god, remember that song?"

But when's the last time you heard Nirvana? I don't think I've heard a Nirvana song since I last listened to one of their CDs in around 1997. Where is the love, people?

I have a theory about why you never hear Nirvana these days. My theory is that Nirvana was a genuinely angry, angry band. And something weird is going on with anger. Something frightening. Anger is disappearing. Or, rather, its being co-opted. It's disappearing among the youth, and being taking over by white middle-aged men who feel like they deserve better and want someone to blame. Old resentment is on the rise; youth anger is on the wane.

Obviously I don't mean private anger, like when you're enraged at your family, friends, and lovers for buying the wrong kind of cookies or ignoring you or posting your secrets on Facebook. That kind of anger will always be with us.

I mean public anger. The anger of rebellion, of why should I play by your stupid rules, of everyone's a goddamn hypocrite, of looking at adults and thinking, how could you people fuck up the world so completely? What the fuck is wrong with you?

I've had occasion to think about this off and on for years, since as a university professor I spend a lot of time with 18-22 year-olds. I'm often surprised by their lack of anger -- at their lack of rebellious rage at their parents, at their institutions, at the world in which they find themselves. Generally, I find today's young people to be temperamentally pretty kind, quite cooperative, and mostly constructively interested in making the world a better place.

Those are all excellent qualities. You could have them and also be angry at the same time. But that's not the feeling I get. The feeling I get is that it would seem stupid, naive, and childish these days to get all riled up and pissed off, to wear crazy punk rock clothes, to raise hell for no reasons, to create a band like The Sex Pistols.

Speaking of which, and as if to prove my point, the Wikipedia entry for The Sex Pistols says that they in 2006 the surviving members refused to attend a ceremony inducting the band into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, quote, "calling the museum 'a piss stain,'" unquote.

I was reminded of the anger situation this morning as I was thinking about the late, great but short-lived Spy Magazine and how there really isn't anything like it any more. Spy was a mix of satire, goofiness, ironic detachment, mean-spirited attacks, vicious take-downs, and actual journalism. I wasn't surprised to learn that the editors cited as an inspiration H. L. Mencken, who personified public anger at pretty much every stage of his life.

When did comedy leave behind "Log-Rolling In Our Time," a regular Spy feature that showcased actual examples of authors giving one another lame mutually adoring blurbs for one another's books, and become Hangover 2?

What do you think the story is? Clearly there's plenty of stuff to be angry about.

Is it that the stuff these days is so overwhelming that it transcends anger, turns in on itself, and becomes anxiety and depression, and that's why there's so many young people on psycho-pharmaceuticals?

Is it that the world has become so frightening and risky -- so stratified, so winner-take-all -- that sheer survival leaves no mental room for anger?

Is it that young people are angry, but anger is too hard to express in their world, in which the internet and social networking make every gesture and every word open to the analysis of everyone on the planet?

Is it all of the above?

So you can see, my theory is that you don't hear Nirvana because Nirvana doesn't fit with our new no-anger youth ethos. I was amused to read today on Wikipedia that Nirvana was considered the "flagship band" of Generation X, of which I am a proud member.

Maybe you remember, we Gen-Xers were supposed to be the great slackers of the world. Everyone was enraged by the way we wanted to just sit around coffeeshops all day (before the internet! we brought books, and paper and pens!), wearing our Doc Martins and smoking cigarettes and talking and shooting the shit, instead of respectably hauling our asses of to McDonalds to get a crappy job.

I've always thought that insofar as this portrait of Gen X was accurate, it actually showed we had good values. We wanted to talk about things; we thought it was an outrage that we'd be paid minimum wage to make crappy burgers for some megachain; and we were willing to have roommates and to live without creature comforts like cars and TVs because we didn't have any money.

It makes me miss the world in which all that was possible. It makes me miss Spy Magazine. And it makes me miss Nirvana.

Monday, July 23, 2012

My Life Force Theory Of Human Nature

|

| L. A. Lakers fans, after a big win. |

Where we are starting with this post: a consideration of some unified theories of human behavior.

In the middle: an explication of that under-recognized and unappreciated force of human existence: The Life Force.

When it comes to theories of human behavior, it always drives me crazy when people say that what humans really want out of life should be understood as just "pleasure" or "happiness."

You hear the first most often when people are talking about motivation, the idea being that humans are primarily motivated by the seeking of pleasure and the avoidance of pain.

You hear the second when people are trying to give big psychology theories about the nature of desire and its role in our lives. There's a whole new mini-cottage industry now of books about happiness and how to achieve it.

But I'm just not buying either of these. Can't you want things knowing they'll bring you displeasure and unhappiness? Think about the last time you broke up with someone, or were broken up with, romantically. In the immediate aftermath, couldn't you have a burning, itchy, crazy desire to call that person, even while knowing that calling them will make you not just miserable but also wildly unhappy?

And I've talked about this before, but can't you sensibly want children even if you are convinced by the studies that show taking care of them is boring and displeasurable and parents are less happy overall than non-parents? If you're thinking about having kids, are pleasure and happiness really the only things you're considering? It seems bizarre to me to think that they would.

Anyway, there is one basic desire, one burning human drive, that these theories always seem to me to leave out. That is: the need to feel alive. I call it The Life Force.

The way the Life Force manifests itself in our modern western culture, when your Life Force is high, you're engaged. You're full of appetites. You want to do stuff: make lentil soup, improve your golf game, learn German. You have a burning desire not only to be alive, but to imprint yourself on the world, to make things happen.

When your Life Force is low, you don't see the point of living. You don't care much what happens. You have no need, or you're afraid, to exert your force, to exert your identity, on the world around you.

If you're at all in thrall to the harmony myth of human nature, you might think that The Life Force is good and its absence is bad. But I don't think that can be right. Because much as The Life Force can be the amazing power of creativity, it can also be the insane passion of rage, or the rabid desire for destruction.

If you're angry at someone and you sink into sadness and depression that is Low Life Force. But if you lash out in a rage, and shout, and throw dishes, that is actually High Life Force: you're imprinting yourself on the world, being you, and making things happen. It's just that those things are bad.

High Life Force might be good for you, but it might be bad for the rest of the world. Because the desire to make things happen, it doesn't really distinguish between the good and the bad. It just wants.

The Life Force involves wanting things, and it is often disturbing to me the way wanting things feels good. Because as we all know, wanting things can be as frustrating as hell. But then when you're faced with the opposite -- with NOT wanting things -- you're like Oh, wait, sorry, can you bring back the wanting please?

The desire to eat more food than is good for you: frustrating. Insufficient desire to eat enough food than is good for you: heartbreaking. Did you ever read stories by cancer patients who've lost their appetite and need marijuana just to be able to eat at all? It makes insufficient desire seem like the saddest thing in the world. Same thing for sex. If you think wanting is bad, think about not wanting for about five minutes. You'll change your mind.

In my theory of The Life Force, the desire, the need, to have The Force, and thus feel that want and desire, is basic and doesn't come from something else. The problem arises when you have it, and now you have this need to make things happen. It's a need that can sometimes be met in a constructive way, but not always.

Everyone's familiar with the pattern when it comes to sex. When you want sex, you feel alive, even if you also feel frustrated. And then if you get to have sex, you're making things happen, and that feels fantastic. After, your Life Force is dissipated, especially if you've had an orgasm. Orgasms: very pleasurable, but they do not add to your life force. After, you have to wait a little for the secret vial in your heart to replenish itself.

The way The Life Force functions in a consumer culture like ours is particularly interesting, because in that culture, shopping mimics the Life Force pattern of sex without the attendant difficulties. You set out: you're wanting, you feel alive. You buy: you're making things happen, and it feels good. After, instead of the dissipation from orgasm, you have clothes/shoes/toys/food to bring home and enjoy. The Life Force just settles itself down very nicely. When you think about it that way, it's not surprising that the average credit card debt in the US is almost 16,000 dollars.

But getting back to the rioting. I don't watch sports, but it is not hard for me to picture the Life Force pattern of important sporting events. Was there ever more of a context for wanting and for feeling alive? But since you're watching, there's not much outlet for making things happen.

If your team loses, your Life Force dissipates and you feel like crap and you have to wait for time to pass for your Life Force to come back. But if your team wins, your Life Force goes through the roof: BAM!. What are you going to do with all that? You've suddenly got to make things happen.

And if you're with eight million other people in exactly the same mood, and you're out on the street, does it surprise you that those things include destroying things and setting cars on fire? Well, it doesn't surprise me.

The pleasure and happiness theories don't do so well explaining the winning rioters. Destroying cars isn't on most people's bucket list, and no one expects it to bring peace and contentment.

But the Life Force theory of human nature makes the whole thing very obvious and clear.

Monday, July 16, 2012

Are Modern Male Novelists Creating Modern Male Losers In Order To Apologize?

|

| Jonathan Franzen, that would be. |

In this recent New York Review of Books article, Elaine Blair argues that there's a new trend among contemporary male American authors: to make guy characters self-abasing, in order to apologize to women readers for those characters' boorish and sexist obsessions with sex and their tendency to objectify women. The apology is needed because it's essential for male readers to be loved by female readers, and female readers were getting irritated by male writers' self-obsession and positive views of their own sexuality.

She traces the framework of the problem back to David Foster Wallace. Wallace's idea was that back in the day, there were the "Great Male Narcissists" (Wallace's term) -- guys like John Updike, Norman Mailer, and Philip Roth. Those GMN's roamed the earth with pride. They relentlessly and unselfconsciously wrote about themselves, and they wrote with candor about sex: about their sexual lives, sexual needs, seductions, and obsessions.

The problem was that in novels of the GMNs, as Blair puts it, "the heroes continue, all the way to the end of their lives, to view sex, apart from love, as a solution for extra-sexual problems—as a balm for everything wrong with life, especially the looming fact of death." The GMNs presented sexual freedom as a cure-all.

This presentation annoyed women, who described Updike in particular with phrases like "penis with a thesaurus." Women mocked and complained. Instead of sexual pride they saw narcissistic boasting; instead of candor they saw boorishness. "So you want to fuck every young thing that comes around?" they said. "And you want us to be all fascinated and admiring? I don't think so."

Blair's idea is that male authors were hurt by this kind of rejection. So they changed tactics, got new strategies. Now, instead of GMNs, you have MMLs: Modern Male Losers (my term). Modern Male Novelists (MMNs) also write about themselves, and also write about sex a lot. But they include an implicit apology for their characters' thoughts in the form of making their characters losers (MMLs). Examples include Gary Shteyngart, Sam Lipsyte, and Jonathan Franzen.

Blair's argument is that there's an implicit appeal from these guys to Ms. Reader: if I show the boors as boorish, you'll still love me, right? Even if the boors can't stop thinking about a woman's breast while she's trying to have a serious conversation?

I should never read these kinds of essays because they make me feel like I'm from Mars.

First: Philip Roth as a "Great Male Narcissists"? I don't like Updike, and I've never read Mailer, but I've read -- and reread -- many of Roth's novels and I'd have said his view is not only different from but is maybe the opposite from the one attributed to him by the GMN narrative.

Yes, Roth's characters are often obsessed with sexual adventurousness, with sexual promiscuity, and with sexual libertinism, and yes, they're obsessed with their own obsessions. But to take the moral as the naive belief that these things will bring The Good Life? As if what makes the Rothians unhappy is their irrational inhibitions? I'd have said the Rothians are in one of the central binds of modern life: what you love, what you need, what makes you feel alive, these are also the things that will kill you, or at least ruin your life. At least if you're not careful. And being careful is impossible.

When Roth's male characters get bored with one woman and have to move on to another, when, heartbreakingly, they don't even get involved with a woman because they know they're going to get bored and leave her, it seems to me the moral is not Oh If Only I Could Sleep Around and Enjoy It but rather This Love and Sex Thing Is Impossible. Ever see a happy lothario in Roth's books? I didn't think so.

It always bothers me, actually, when people say Roth's books are "about sex." Because yeah, on one level sure, they're about sex. But to me they're about sex as a mere instantiation of this deeper problem, which, if you consider it abstractly, is the problem of death: it's the problem of feeling alive, and what that does to you.

Second: It's never been clear to me why the fact of thinking about sex, or having sex a lot, or having it with a lot of different people, is in itself boorish or sexist. From what I understand, many gay men think about and have sex a lot, often with different people. If we're talking about men with other men, presumably this isn't instantiating sexism. Is it instantiating boorishness? I guess it could. But it doesn't in general. It might be boorish only if you were doing something like constantly trying to push someone into having sex with you, or thinking only about sex when someone's trying to talk about something serious and not sexy. If there's a problem, it doesn't seem like a quantity problem. It's a context problem.

Plausibly, context is one of the things people are noticing and complaining about in the GMN and MML narrative. Blair cites a passage from The Corrections in which an MML writes an awful screenplay and as his girlfriend is breaking up with him she explains that among other things, the screenplay is full of boorish breast references. "For a woman reading it," she says, "it’s sort of like the poultry department. Breast, breast, breast, thigh, leg." This MML, Blair says, "has completely failed to understand the female point of view." "His humiliations will be many."

But this brings me to --

There's a scene I love in Sam Lipsyte's novel The Ask in which a man goes to drop off his kid at the day care center and finds that it's closed, and he runs into a woman also trying to drop off her kid. His marriage is falling apart, and he interprets their exchange as intense flirting, fully expecting that after their conversation they'll head back to her place for sex while the kids watch a video or something. Of course, she has nothing like that in mind. Of course, she just says goodbye.

If this guy is thinking about sex, then fails to understand the female point of view, and then is humiliated, isn't it more likely that Lipsyte thought the interconnected thinking, failing, and humiliation are characteristic of life as a modern man than that he was implicitly apologizing to his female reader for presenting a guy obsessed with thinking about sex?

There's some other stuff, but I'll stop here. Putting it all together, I think the answer to the question of the title is No, Modern Male Novelists Are Not Creating Modern Male Losers In Order To Apologize.

They're not pursuing a literary tactic. They're trying to understand something real and important about modern life, about masculinity, about how to live well, about relations between men and women. And they're succeeding.

Monday, July 9, 2012

Why Isn't Shouts and Murmurs Funny? Or, My LTR With The New Yorker

The New Yorker and I are definitely in what you might call a Long Term Relationship (LTR). This is no one night stand, and it's no casual fling. It's not an on-again-off-again thing. It's not a case of FWB. We're committed.

This relationship started when I was about nine years old. The New Yorker had always been around our home when I was a kid, and for years I had regarded it the same way I'd regarded Masterpiece Theater, the Watergate hearings, and the Phil Donahue show: something clearly for grownups, something probably boring, something I hoped I wouldn't have time for in my future life as a rock star or rock-star-equivalent.

That slight disdain changed one day when I picked it up in a moment of having nothing else to do, and I found Ved Mehta. My eye just happened to land right in the middle of his memoir about being a young blind boy in India, living away from his parents at a special school.

I was immediately gripped and fascinated. Living away from one's parents as a young child? Having to relearn how to do everything without sight? Having to use braille for the simple act of reading? These were challenges I could barely fathom. And Mehta wrote about them with the heartfelt simplicity that engages both the New York literati (or so we can imagine, this being The New Yorker) and me, a nine year old girl living comfortably in the bland American suburbs. I was hooked.

There were certainly phases during my youth in which I was inattentive, but I'd say over the last fifteen years or so I've barely missed an issue. There have been times when I've been tempted to regard The New Yorker in the light of a life saver. I seldom feel "at home" in a place, and I've lived a lot of places where I felt like a freak. This can be seriously discouraging. But I could always come home, uncork a bottle of wine, and open The New Yorker, and feel at home in the world through the powerful reminder: there are, in fact, other people like me.

There are other people who want to read long articles about Chinese race car drivers, Dickens camp, the cutting edge of food technology, and therapy trends among the Hollywood glitterati. There are other people who care about the politics of apple branding (the fruit, not the computer). Wanting to know more about the state of soccer mania in Turkey does not make me impossibly strange.

It's because The New Yorker and I have an LTR and not a casual friendship that I got disturbed by the following problem: Why isn't Shouts and Murmurs Funny? If you don't know, Shouts and Murmurs is the humor part of The New Yorker. Obviously many articles in The New Yorker are funny in their various ways. But Shouts and Murmurs is supposed to be The Funny Page. Sometimes it's funny. But often, it's not.

I like funny. Don't I like funny? And as we now know, I love The New Yorker. So how could I not like The Funny Page of The New Yorker?

I thought the problem might just be stylistic. The writing in Shouts and Murmurs tends to take a single joke and make a page of writing about it. I don't really go for that. Once you see the joke, in the first paragraph, you're like OK, kinda funny. But there's still a lot left to read.

But I was talking the matter over with my friend, and he said he didn't think it was stylistic at all. He said that the problem with Shouts and Murmurs is part of a deep problem with the whole New Yorker, and with its whole way of seeing and writing about the world.

Shouts and Murmurs, he said, is almost always a kind of mini-parody of something, or a little riff on a familiarity, poking a gentle bit of fun. Like this week it mocks the escalation of high-end-restaurant-waiter-palaver. That's very typical. What it doesn't do is take any kind of stand, for or against something. But that's The New Yorker all around. Always safe, always middle of the road, never fired up with indignation and rage.

I was a little shocked. I defended The New Yorker. I pointed out that Elizabeth Kolbert often presents highly opinionated views of her own, written up in a style sure to piss some people off. Her review of Stephen Pinker's book about violence was one of the only reviews I saw that wasn't largely ass-kissing fluff. I said that sometimes you don't want opinionated ranting, indignation and rage. Like when you're reading about Chinese race car drivers, or cutting edge trends among the Hollywood glitterati, or the politics of apple branding. Those articles have points of view but they also try to just tell you some stuff, some stuff you didn't know, that you may find interesting. I really go for that.

Eventually we agreed that while Elizabeth Kolbert was often highly opinionated, that wasn't the characteristic style of The New Yorker, and that in certain contexts, like politics, that could be a problem. But we also agreed that in a world that is all political indignation all the time, telling you some stuff you didn't know was important too. The rest of is a matter of taste. I have enough indignation going on inside me all the time. Encountering it in my reading can be too too much. Evidently, I really like to just be told some stuff I didn't know, some stuff I may find interesting.

I had to agree with my friend about Shouts and Murmurs, though. He's right. Comedy can't be mush. It has to take a stand, or tell the truth, or be really personal, or surprise you somehow, to be really funny. The mini-parodies, the riffs, the gentle bit of fun of Shouts and Murmurs mostly don't do any of those things.

This relationship started when I was about nine years old. The New Yorker had always been around our home when I was a kid, and for years I had regarded it the same way I'd regarded Masterpiece Theater, the Watergate hearings, and the Phil Donahue show: something clearly for grownups, something probably boring, something I hoped I wouldn't have time for in my future life as a rock star or rock-star-equivalent.

That slight disdain changed one day when I picked it up in a moment of having nothing else to do, and I found Ved Mehta. My eye just happened to land right in the middle of his memoir about being a young blind boy in India, living away from his parents at a special school.

I was immediately gripped and fascinated. Living away from one's parents as a young child? Having to relearn how to do everything without sight? Having to use braille for the simple act of reading? These were challenges I could barely fathom. And Mehta wrote about them with the heartfelt simplicity that engages both the New York literati (or so we can imagine, this being The New Yorker) and me, a nine year old girl living comfortably in the bland American suburbs. I was hooked.

There were certainly phases during my youth in which I was inattentive, but I'd say over the last fifteen years or so I've barely missed an issue. There have been times when I've been tempted to regard The New Yorker in the light of a life saver. I seldom feel "at home" in a place, and I've lived a lot of places where I felt like a freak. This can be seriously discouraging. But I could always come home, uncork a bottle of wine, and open The New Yorker, and feel at home in the world through the powerful reminder: there are, in fact, other people like me.

There are other people who want to read long articles about Chinese race car drivers, Dickens camp, the cutting edge of food technology, and therapy trends among the Hollywood glitterati. There are other people who care about the politics of apple branding (the fruit, not the computer). Wanting to know more about the state of soccer mania in Turkey does not make me impossibly strange.

It's because The New Yorker and I have an LTR and not a casual friendship that I got disturbed by the following problem: Why isn't Shouts and Murmurs Funny? If you don't know, Shouts and Murmurs is the humor part of The New Yorker. Obviously many articles in The New Yorker are funny in their various ways. But Shouts and Murmurs is supposed to be The Funny Page. Sometimes it's funny. But often, it's not.

I like funny. Don't I like funny? And as we now know, I love The New Yorker. So how could I not like The Funny Page of The New Yorker?

I thought the problem might just be stylistic. The writing in Shouts and Murmurs tends to take a single joke and make a page of writing about it. I don't really go for that. Once you see the joke, in the first paragraph, you're like OK, kinda funny. But there's still a lot left to read.

But I was talking the matter over with my friend, and he said he didn't think it was stylistic at all. He said that the problem with Shouts and Murmurs is part of a deep problem with the whole New Yorker, and with its whole way of seeing and writing about the world.

Shouts and Murmurs, he said, is almost always a kind of mini-parody of something, or a little riff on a familiarity, poking a gentle bit of fun. Like this week it mocks the escalation of high-end-restaurant-waiter-palaver. That's very typical. What it doesn't do is take any kind of stand, for or against something. But that's The New Yorker all around. Always safe, always middle of the road, never fired up with indignation and rage.

I was a little shocked. I defended The New Yorker. I pointed out that Elizabeth Kolbert often presents highly opinionated views of her own, written up in a style sure to piss some people off. Her review of Stephen Pinker's book about violence was one of the only reviews I saw that wasn't largely ass-kissing fluff. I said that sometimes you don't want opinionated ranting, indignation and rage. Like when you're reading about Chinese race car drivers, or cutting edge trends among the Hollywood glitterati, or the politics of apple branding. Those articles have points of view but they also try to just tell you some stuff, some stuff you didn't know, that you may find interesting. I really go for that.

Eventually we agreed that while Elizabeth Kolbert was often highly opinionated, that wasn't the characteristic style of The New Yorker, and that in certain contexts, like politics, that could be a problem. But we also agreed that in a world that is all political indignation all the time, telling you some stuff you didn't know was important too. The rest of is a matter of taste. I have enough indignation going on inside me all the time. Encountering it in my reading can be too too much. Evidently, I really like to just be told some stuff I didn't know, some stuff I may find interesting.

I had to agree with my friend about Shouts and Murmurs, though. He's right. Comedy can't be mush. It has to take a stand, or tell the truth, or be really personal, or surprise you somehow, to be really funny. The mini-parodies, the riffs, the gentle bit of fun of Shouts and Murmurs mostly don't do any of those things.

Monday, July 2, 2012

The Ethical Complexity Of Being Judgey

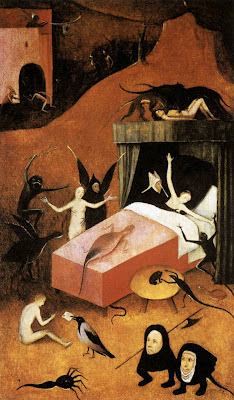

_-_WGA02578.jpg) |

| Hieronymus Bosch - Last Judgment (fragment of Hell), via Wikimedia Commons. |

Certainly there's a powerful contingent out there who thinks the answer is No. They say: "Don't judge me!" "Don't be judgey!" and, as I just learned from the Google, "Don't be a judgey McJudgerson!"

I get this sentiment, I really do. It's got a very appealing kind of "live and let live" aspect. And many reasons people are judgmental really are stupid. Sometimes the just world fallacy makes people judgmental: Oh, she got cancer? She must have eaten meat/used cosmetics/stressed herself out/not been careful about BPAs. Some people are so careless! Thank heaven I would never do such a thing." Moronic.

But some of the reasons we're judgmental are complicated, because they stem from the following important fact: other people's choices structure your cultural environment.

For a simple example, suppose you have -- bushy eyebrows, like the guys in this article, and suppose you like them. In our world, you have two choices. You can shape/pluck/wax etc, and look normal. Or you can refrain, and be considered a freak/weirdo/non-conformist. Notable not on your list of options is the combination of doing nothing and having nobody care.

Sure this is partly because "THEY" decided bushy eyebrows were bad or something. But all it takes is everyone else doing it to make not doing it make you a freak. Wearing a robe around outside isn't "bad" in our world but you can't do it and not be a freak. You don't have that option. And the reason you don't have that option is because other people's choices structure your cultural environment.

Considered alone this social aspect of choices might not be such a big deal: we live in a social world, etc etc blah blah blah.

But it can't be considered alone. Because we live in a world of arms races. And in a world of arms races, the social aspects of choices make everyone's business everyone else's business.

A couple of weeks ago The New York Times ran this article about the increasing use of Aderall among high school students who want to study more effectively. It had all the predictable New York Times-y elements: anecdotes about ivy-league aspirants, interviews with child psychologists, a vivid description of a kid snorting crushed Adderall just before the SAT.

You don't have to read the article to see the obvious. If everyone in your school takes Adderall, and if Adderall improves school performance, and if getting into a well-regarded university is hyper-competitive, well ... you'd better find a way to take it too, no?

The US, always a world leader when it comes to trends for what is awful, is already a winner-take-all society, with haves and have-nots, no one in between, and the life of the have-nots an increasing hell. In this atmosphere, academic achievement is an arms race: it's rational to "spend" whatever you need to. So if everyone else is taking drugs, the price you'd better be willing to pay is clear: you'd better take the Adderall.

Maybe you're thinking, Well, sure, of course it's appropriate to judge drug-takers. They're taking drugs! They're pretending to have symptoms; they're buying from other students; it's ethically dubious in any case.

But there's lots of cases where the innocuous choices of other people structure our choices in ways we don't want. People are always talking about work-life balance, and about the needs of parents to have flexible work time, and about the disproportionate way the burdens of parenting fall on women, to their career detriment.

These are all serious and important problems. But they're often talked about through the vague idea of "norms" and "attitudes." Like, we need to shift norms and attitudes so it is "OK" to take time for your family, to go home for dinner, to leave work for the kids' soccer games or whatever.

But the fact that other people's choices structure your cultural environment means that the problem goes far deeper than norms and attitudes. Even if the managerial classes of America were to have a sudden conversion experience all at the same time -- and here I picture maybe some ESP rays starting at a TED talk and emanating through the bluetooth connections of the world -- a conversion experience of believing in the power and importance of Dinner Together and Piano Lessons at Four, sure that would help, but would it solve the problem?

I don't think so. In "merit-based" arms race competitive culture like ours, you often get ahead by being able to do more of what someone wants you to do. If half the population is willing to have no life outside work so that they're going to do more of those things, in the nature of things they're going to get ahead. It's partly their choices that determine what seems like "being available" and being "a team player" and being "committed to the job."

This problem seems to me much harder than the changing norms and attitudes problem, difficult as that one is.

About a year ago (I think) The Times also reported a huge increase in women getting "blowouts" -- this is where you make time in your day, not to get your hair cut, but just to get it washed and styled. I was appalled. Not because I think people should have curly hair, and not because I'm against beauty treatments, but just because in the arms race what counts as proper, neat-looking, professional looking hair, this was a sudden ramping up. A ramping up I do not need or want.

It's just like the Adderall. If a twice-weekly hair blowout becomes the new standard for looking properly put together, that is going to suck.

So yeah. Of course: your hair, your choice. But also: twice weekly blow-outs? Give me a break.

When you look at it this way, it's not surprising that we're all silently judging one another.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)