_-_WGA02578.jpg) |

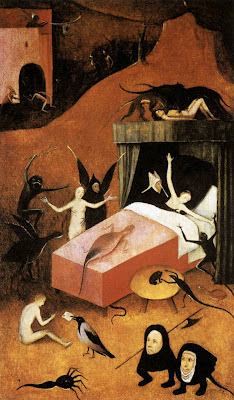

| Hieronymus Bosch - Last Judgment (fragment of Hell), via Wikimedia Commons. |

Certainly there's a powerful contingent out there who thinks the answer is No. They say: "Don't judge me!" "Don't be judgey!" and, as I just learned from the Google, "Don't be a judgey McJudgerson!"

I get this sentiment, I really do. It's got a very appealing kind of "live and let live" aspect. And many reasons people are judgmental really are stupid. Sometimes the just world fallacy makes people judgmental: Oh, she got cancer? She must have eaten meat/used cosmetics/stressed herself out/not been careful about BPAs. Some people are so careless! Thank heaven I would never do such a thing." Moronic.

But some of the reasons we're judgmental are complicated, because they stem from the following important fact: other people's choices structure your cultural environment.

For a simple example, suppose you have -- bushy eyebrows, like the guys in this article, and suppose you like them. In our world, you have two choices. You can shape/pluck/wax etc, and look normal. Or you can refrain, and be considered a freak/weirdo/non-conformist. Notable not on your list of options is the combination of doing nothing and having nobody care.

Sure this is partly because "THEY" decided bushy eyebrows were bad or something. But all it takes is everyone else doing it to make not doing it make you a freak. Wearing a robe around outside isn't "bad" in our world but you can't do it and not be a freak. You don't have that option. And the reason you don't have that option is because other people's choices structure your cultural environment.

Considered alone this social aspect of choices might not be such a big deal: we live in a social world, etc etc blah blah blah.

But it can't be considered alone. Because we live in a world of arms races. And in a world of arms races, the social aspects of choices make everyone's business everyone else's business.

A couple of weeks ago The New York Times ran this article about the increasing use of Aderall among high school students who want to study more effectively. It had all the predictable New York Times-y elements: anecdotes about ivy-league aspirants, interviews with child psychologists, a vivid description of a kid snorting crushed Adderall just before the SAT.

You don't have to read the article to see the obvious. If everyone in your school takes Adderall, and if Adderall improves school performance, and if getting into a well-regarded university is hyper-competitive, well ... you'd better find a way to take it too, no?

The US, always a world leader when it comes to trends for what is awful, is already a winner-take-all society, with haves and have-nots, no one in between, and the life of the have-nots an increasing hell. In this atmosphere, academic achievement is an arms race: it's rational to "spend" whatever you need to. So if everyone else is taking drugs, the price you'd better be willing to pay is clear: you'd better take the Adderall.

Maybe you're thinking, Well, sure, of course it's appropriate to judge drug-takers. They're taking drugs! They're pretending to have symptoms; they're buying from other students; it's ethically dubious in any case.

But there's lots of cases where the innocuous choices of other people structure our choices in ways we don't want. People are always talking about work-life balance, and about the needs of parents to have flexible work time, and about the disproportionate way the burdens of parenting fall on women, to their career detriment.

These are all serious and important problems. But they're often talked about through the vague idea of "norms" and "attitudes." Like, we need to shift norms and attitudes so it is "OK" to take time for your family, to go home for dinner, to leave work for the kids' soccer games or whatever.

But the fact that other people's choices structure your cultural environment means that the problem goes far deeper than norms and attitudes. Even if the managerial classes of America were to have a sudden conversion experience all at the same time -- and here I picture maybe some ESP rays starting at a TED talk and emanating through the bluetooth connections of the world -- a conversion experience of believing in the power and importance of Dinner Together and Piano Lessons at Four, sure that would help, but would it solve the problem?

I don't think so. In "merit-based" arms race competitive culture like ours, you often get ahead by being able to do more of what someone wants you to do. If half the population is willing to have no life outside work so that they're going to do more of those things, in the nature of things they're going to get ahead. It's partly their choices that determine what seems like "being available" and being "a team player" and being "committed to the job."

This problem seems to me much harder than the changing norms and attitudes problem, difficult as that one is.

About a year ago (I think) The Times also reported a huge increase in women getting "blowouts" -- this is where you make time in your day, not to get your hair cut, but just to get it washed and styled. I was appalled. Not because I think people should have curly hair, and not because I'm against beauty treatments, but just because in the arms race what counts as proper, neat-looking, professional looking hair, this was a sudden ramping up. A ramping up I do not need or want.

It's just like the Adderall. If a twice-weekly hair blowout becomes the new standard for looking properly put together, that is going to suck.

So yeah. Of course: your hair, your choice. But also: twice weekly blow-outs? Give me a break.

When you look at it this way, it's not surprising that we're all silently judging one another.

No comments:

Post a Comment